The Life & Times o f Lou is L omax The Art of Deliberate Disunity

Thomas Aiello

t h e li fe & t i mes o f l o u is l o m ax

The Life & Times of Louis Lomax t h e a rt o f d eli b er at e disun it y

Thomas Aiello duke university press Durham & London 2021

© 2021 duke university press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro and Scala Sans Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Aiello, Thomas, [dates] author. Title: The life and times of Louis Lomax : the art of deliberate disunity / Thomas Aiello. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2020021674 (print) | lccn 2020021675 (ebook) | isbn 9781478010685 (hardcover) | isbn 9781478011804 (paperback) | isbn 9781478013150 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Lomax, Louis E., 1922–1970. | African American journalists—United States— Biography. | African Americans in television broadcasting—United States—Biography. Classification: lcc pn4874.l5925 a934 2021 (print) | lcc pn4874.l5925 (ebook) | ddc 070.92 [b]—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov /2020021674 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov /2020021675

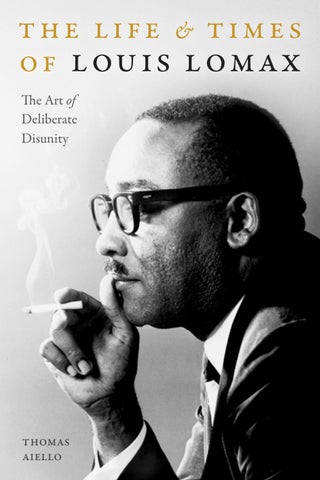

Cover art: Louis Lomax, ca. 1960. Courtesy Special Collections and University Archives of the University of Nevada, Reno. Item 82-30-6-10-1.

produced with a grant from Figure Foundation publication of the global nation

Yes, my dear brethren, when I think of you which very often I do, and the poor despised miserable state you are in, when I think of your ignorance and stupidity and great wickedness of the most of you, I am pained to the heart.

jupiter hammon, 1786

Contents

acknowledgments

xi

Introduction

1

1

From Privilege to Prison

7

2

The Hate That Hate Produced

24

3

The Reluctant African

40

4

The Negro Revolt

55

5 Ambitions

73

6 When the Word Is Given

90

7 The Louis Lomax Show

111

8 Thailand

132

9

150

Branching Out

10 Conspiracies

167

notes

179

bibliography

221

index

239

Acknowledgments

As with any book, so many people have helped in its construction that I cannot name them all h ere. But I would particularly like to single out the staff of the Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Nevada, Reno. Jacquelyn Sundstrand went above and beyond to help me navigate a collection that was unprocessed when I began this project. It is, in some sense, a mystery as to why Lomax’s widow chose unr to house his papers. Lomax had no specific connection with the city or the university. But they are t here, and they are now organized and available thanks to the hard work of Jacquelyn and her colleagues. She worked to process the collection even as I was sitting in the reading room reviewing the documents themselves. This book uses a variety of archival collections, of course, but it understandably relies most heavily on those from Lomax’s personal papers. The book thus would not exist without Jacquelyn and the archivists at unr. I hope that this book serves as a testament to their hard work and diligence.

Introduction

Louis Emanuel Lomax was an ex-con who served time in Illinois’s Joliet Correctional Center for a confidence scheme of selling rented automobiles to used car dealers. He had uncontested domestic abuse claims on his record, two arrests for driving under the influence, and four divorces. He lied publicly about his collegiate education on a regular basis. Constantly in search of fame and media attention, he ingratiated himself to popular leaders on the fringes of both sides of the political spectrum and changed his position on key social issues when it suited his interest or audience. He criticized every major civil rights leader, engaged in hopeless assassination conspiracy theories, and took advantage of violent conflicts, both domestic and international, to draw attention to himself. In 1963, while giving the John B. Russworm Lecture at the California Negro Leadership Conference at Stanford, he told his audience that they needed to develop “the art of deliberate disunity,” criticizing “the state of Negro euphoria, that seizure of silly happiness and emotional release that comes in the wake of a partial civil rights victory.”1 No, wait. Louis Emanuel Lomax rose from a childhood in the deepest of the Deep South, Valdosta, Georgia, to become one of the most successful Black journalists of the twentieth c entury. He introduced Malcolm X to the nation and remained a close ally of both Malcolm and Martin Luther King Jr. for the duration of their lives. He helped organize the 1968 Olympic boycott and was with Harry Edwards at the event’s initial press

conference. He was in the nation’s capital for the success of the March on Washington and the confusion of Resurrection City. He was the opening act for Malcolm X’s “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech and was on the telephone with Betty Shabazz the night he was killed. As the first Black man to host a syndicated television talk show and as the author of several best-selling and influential books, he was both a driver and a popularizer of virtually every element of the civil rights movement from the late 1950s to the late 1960s. In 1963, while giving the John B. Russworm Lecture at the California Negro Leadership Conference at Stanford, he told his audience that they needed to develop “the art of deliberate disunity,” emphasizing that “only through diversity of opinion can we establish the basic prerequisite for the democratic process.”2 Lomax told his Stanford audience that he wanted civil rights leaders to begin emphasizing economic and educational concerns, the building of infrastructure within the community that would allow the Black population to take advantage of any future political gains. He worried aloud about infighting in the movement, wherein competing groups jockeyed for power in an effort to become the public face of civil rights. It was a call for unity even as it defended functionally radical positions within the movement, a seemingly contradictory argument made all the more palatable because it contained something that appealed to everyone. It was sound and fury, signifying both nothing and everything, and it was a case made by someone who actively sought the spotlight and the potential power that came with it. In that sense, Lomax’s Stanford speech reflected the broader scope of his life. He was a publicity-seeking provocateur who did what he could both to report on the news and to keep himself in it. That effort made him one of the loudest and most influential voices of the 1960s civil rights movement and Black foreign policy journalism. Domestically, Lomax tended to argue for integrationism as a v iable civil rights goal, though that position vacillated throughout his c areer. Yet one of his closest friends and allies was Malcolm X. Their relationship was built on the reciprocal benefits they could provide, each the ideological foil for the other at various moments, but they w ere also real friends, and Lomax’s classical southern understanding of integrationist civil rights evolved over the years b ecause of his proximity to Malcolm, the Nation of Islam (noi), and Black nationalist thinking. His thinking took a circular trajectory, beginning at the classical rights understanding of a Black southerner from Valdosta before finding a more nationalist position a fter his long association with Malcolm. Though he never abandoned his 2 · Introduction

admiration for the noi’s leader, Lomax’s public thinking about race rights turned more pragmatic in the last five years of his life, following Malcolm’s 1965 assassination, and his philosophical evolution ultimately took him back close to where he had begun. That play of Malcolm on Lomax also worked in reverse, with the journalist accompanying Malcolm at his most seminal and career-defining moments. Lomax was a study in contradictions. “We need a revolution in this country,” he declared in the late 1960s. Then he demurred by describing what he called a “revolution by education,” emphasizing Black studies as a strong start that needed to filter down to primary and secondary education. He insisted that he was in favor of nonviolence but then explained, “The American white man—like all white men—only understands vio lence.” The white man was “the epitome of violence.” Whites in general were “a racist, violent p eople.” Even with such an assessment, he supported integration, while at the same time calling for a total restructuring of the American economy. “Some w ill no longer be able to luxuriate with four automobiles and five garages while o thers have nothing,” he said. “You can’t tell a man work is virtue but there are no jobs so he goes to hell by default.” Lomax predicted a new revolution in 1976, two hundred years after the first one. Although the revolution never occurred, and Lomax did not even live to see the bicentennial, it was not an unreasonable prediction. For all of his bravado, he possessed a pragmatic willingness to shift positions in response to changing situations and in pursuit of his own success, as well as a keen ability to diagnose the problems the country faced. “America is fundamentally a country of style rather than substance,” he ere, into the parking lot, and find said. “I’ll bet we could walk out of h that nine-tenths of the people flying the flag have no intention of doing what the flag stands for.”3 His dual mission, as he saw it, was to call out that nine-tenths while playing a game of style over and against one of substance. Lomax’s life was an argument that you could not do the former without doing the latter. His foreign policy thinking was much the same. If Pan-Africanism existed on one end of the ideological Black foreign policy spectrum and noninterventionist calls for peace in Vietnam existed on the other, Lomax found himself moving between t hose two poles. His most consistent message in this regard—and the one that seemed to bridge the ideological divide—was an opposition to colonialism that pushed back against resource extraction and economic hegemony in Africa and Asia. Lomax tended to avoid comparative models in favor of analyzing individual Introduction · 3

regions and leaders in their specific cultural context. That said, Lomax was a popularizer of anticolonial movements, a freelance journalist with an ideological and financial interest in his presentations, but he was a layperson, and his accounts of conflicts in various parts of Africa, Thailand, and Vietnam often lacked the nuance of scholars steeped in the history of those regions and their relationships with the West. Continuing his general inconsistency, he advocated peace while defending indigenous military action as a salve against colonial intervention; continuing his bent for sensationalism, he often ignored detailed intricacy in favor of wide-scale conclusions to make his arguments. Such was the nature of a self-promoting novice with deep-felt concerns about the well-being of the people he covered. Lomax’s consistent efforts to find this ideological third way would be both a blessing and a curse. He was consistent in his contradictions but not in his analysis of events. By using a broad-brush approach to paint the symptoms of systemic racism rather than more nuanced but less interest ing causes, Lomax kept himself in the public eye, thereby making himself an effective mainstream advocate for Black issues. But despite his central role in that advocacy—his position at the forefront of so many of the civil rights movement’s pivot points—those contradictions left his legacy at the historical margins. They made his role in the movement harder to interpret and eventually harder for historians to see at all. Thus, while he is almost always featured in a tertiary role in accounts of the 1960s civil rights movement, he has never been given pride of place. The same can be said for accounts of American foreign policy in Africa and Asia during the decade. But Lomax was central to the era’s civil rights movement, and while he was not central to American foreign policy in any way, he was decidedly influential in popularizing the situations in sub-Saharan Africa and southeast Asia. Lomax was also one of the most important journalists of the decade, helping to cement the career of Mike Wallace, setting precedents for Black journalism in radio and television, and maintaining a literary profile that included newspaper reporting, long-form magazine journalism, and the best-selling books The Reluctant African and The Negro Revolt. This volume moves Lomax to the center of the civil rights narrative of the 1960s, describing his particular “art of deliberate disunity” and the influence it had on the decade’s journalism, its civil rights activism, and its public thinking about foreign policy. He was in many ways both created by the national tumult of the 1960s and a creator of many of its seminal 4 · Introduction

moments. His thinking would always be pragmatic, willing to change with perceived necessity to remain influential or controversial or to support rights activism. The trajectory of that thought was riddled with inconsistencies, but it mirrored the inconsistencies of a country in the throes of dramatic change, as the hypocrisy of America and of Lomax worked in a reciprocal relationship to create a nation more open to Black journalism, more willing to provide racial equality, less tolerant of global colonialism, and ultimately (and ironically) less hypocritical. His inconsistencies were his own, as were his lies and crimes. But they were also, in their way, America’s inconsistencies. And they never stopped him from his consistent and beneficial advocacy for Black rights. Lomax’s story is unique, but it is also representative—a contradiction that the controversial journalist would surely find fitting.

Introduction · 5

Notes

abbreviations adw — Atlanta Daily World baa — Baltimore Afro-American bg — Boston Globe cd — Chicago Defender ct — Chicago Tribune fbi File No. 62-102926 —Louis Lomax, fbi Central Headquarters File, 62-102926, foia, Federal Bureau of Investigation fbi File No. 100-399321 —Malcolm Little (Malcolm X), fbi Central Headquarters File, 100-399321, foia, Federal Bureau of Investigation Illinois v. Lomax — Illinois v. Louis Lomax, case no. 49CR-2439, 49CR-2440, 49CR-2441, Files of the Criminal Court of Cook County, Office of the Clerk of Court, Chicago King Assassination Documents —King Assassination Documents—fbi Central Headquarters File, Assassination Archives and Research Center, Washington DC las —Los Angeles Sentinel lat —Los Angeles Times Lomax File —Louis Emanuel Lomax student file, Registrar’s Office, Paine College, Augusta, GA Lomax Papers —Louis E. Lomax Papers, 82-30, Special Collections, University of Nevada, Reno nyan — New York Amsterdam News nyht — New York Herald Tribune nyt — New York Times pc — Pittsburgh Courier wp — Washington Post

introduction 1 las, 29 August 1963, A9, C3. 2 las, 29 August 1963, A9, C3. 3 Undated interview, box 1, series 1, subseries 3, folder 2, Lomax Papers.

1. from privilege to prison 1 Macedonia First Baptist Church now rests at 715 J. L. Lomax Drive. Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900, Population Schedule, Valdosta District, Lowndes, Georgia, Sheet No. 53a; Valdosta Daily Times, 6 November 1933, 5; Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910, Population Schedule, Valdosta District, Lowndes, Georgia, Sheet No. 8b; Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920, Population Schedule, Valdosta, Lowndes, Georgia, Sheet No. 11a. 2 Vieth, “Kinderlou.” For more on the historical development of Valdosta and Lowndes County, see Schmier, Valdosta; Shelton, Pines. 3 Boyd, Blind Obedience, 97–108 (quote from 105). 4 It would later be known as Georgia Baptist College. Beset by financial woes, it closed in 1956. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920, Population Schedule, Valdosta, Lowndes, Georgia, Sheet No. 11a; Manis, Macon, 51, 80. 5 Emanuel Curtis Smith and Sarah Louise Lomax, Marriage License, Bibb County, Georgia, 464, retrieved from Ancestry.com; Emanuel Curtis Smith, Registration Card, World War II, Serial No. 464, Order No. 10144, Local Board for the County of Wilcox, Abbeville, Georgia, retrieved from Ancestry.com. The fbi wrongly placed Emanuel Smith’s birthplace in Sandersville, Georgia, in Washington County. While it was an understandable mistake given the number of small towns in central Georgia and poor record keeping by white officials, it is notable that Sandersville was in fact the birthplace of Elijah Poole, later known as the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, who also played a considerable role in Lomax’s life. “Louis Emanuel Lomax: Internal Security—Cuba,” 4 October 1963, fbi File No. 62-102926. 6 Later in the 1920s, Lomax’s father married teenager Louisa Watkins, eleven years his junior, and had two c hildren with her. He then moved to neighboring Dodge County, where he lived u ntil his death on 1 January 1963. baa, 19 August 1961, 19; Emanuel Curtis Smith, Registration Card; Emanuel C. Smith, Georgia Death Index, 1919–1998, Certificate No. 00473, Office of Vital Records; Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population Schedule, Militia District 1254, Dodge, Georgia, Sheet No. 10a; Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940, Population Schedule, Mitchell, Dodge, Georgia, Sheet No. 8a; Manuel Smith, US Social Security Applications and Claims Index, Social Security Administration; Sarah Smith, Georgia Death Index, 1919–1998, Certificate No. 2320106, Office of Vital Records. 7 Myers, “Killing.” See also Buckner, Mary Turner. 180 · Notes to Introduction